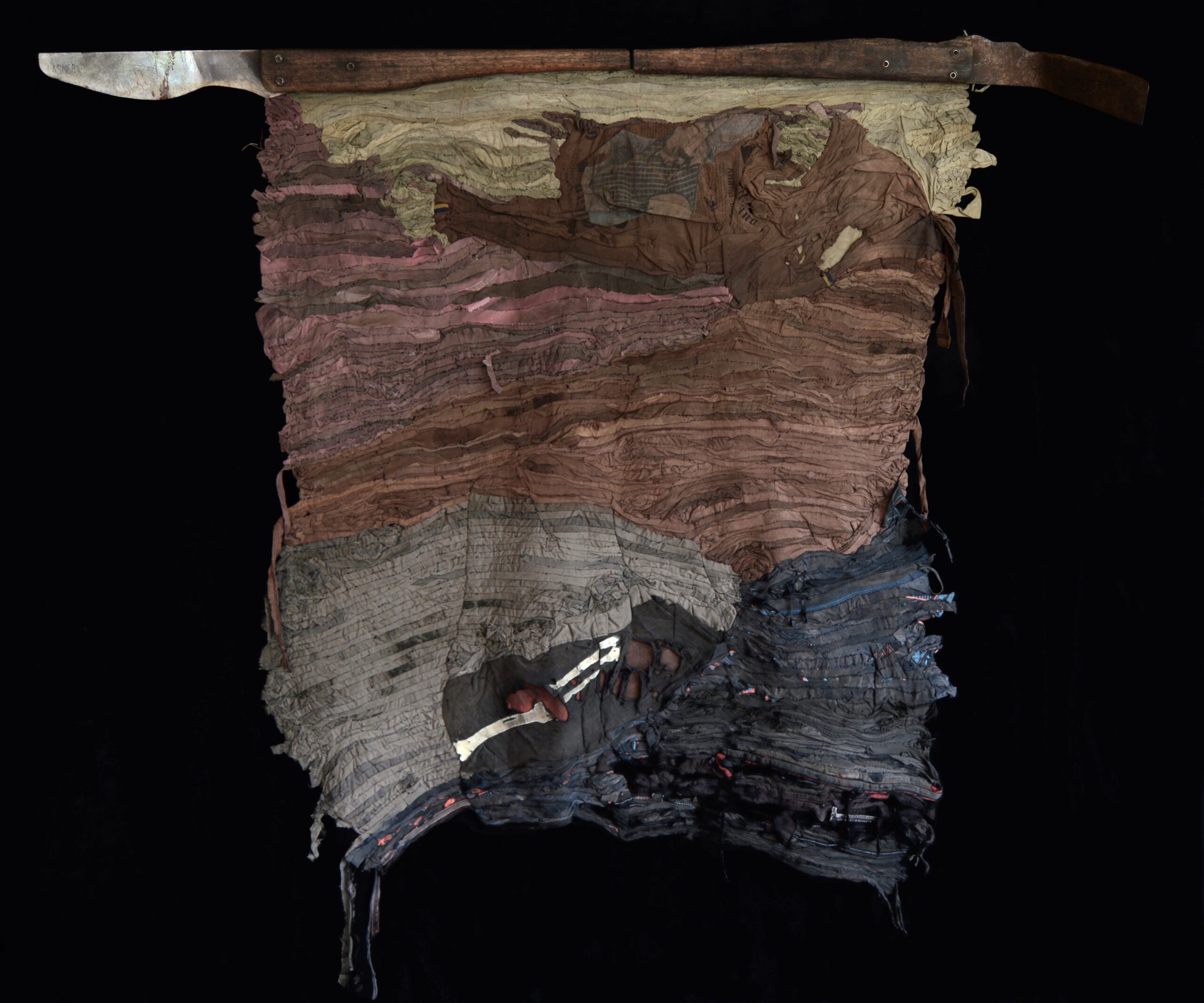

Man IV

145cm x 120cm

Pastel and charcoal on wooden board

2016

I

was welcomed into a misty morning of medieval romanticism. The

figures around me were all dressed in rags of variable styles and

gender objectives.

Layers upon layers of shirts and pants, with the last layer often

being a dress thrown over everything. Narrow fitting Jean skirts

were, strangely enough,

the norm, although I

don't know how anyone can move in a thing like that. I guess they all had

pretty long slits at the back.

Heads

were often hooded and necks scarved. Either a rubber sleeve, stretching from wrist to elbow, and fastened with thin

rubber lacing pulled through hand made eyelets

or layers and layers of

scarves and cloth covered the

non-dominant arm. This

was important because the scooping arm took the brunt of pokes and

scratches when handling sugarcane.

Being in

fact, nothing other than an

enormous species

of grass it has the

ability of inflicting grass cuts,

similar to paper cuts, in the world that we live in. After this, worker's boots

without which no-one

could navigate the uneven terrain and still produce his or her

quota. And finally the dreaded panga (slashing knife), of which many a

horror story of implementation to harm or murder have circulated our media. The knight's

trusted sword or grim reaper's dreaded scythe. It was otherworldly,

but had nothing to do

with a film set or

the latest copy of Bazaar.

All this are totally functional and were invented

by the workers for self

protection against nasty cuts

and lurking snakes.

They work in rows, one man per row and aim to do six rows in a shift. Or they work as a couple, man and wife. The man most often doing the cutting and the wife the stacking. By the end of the session a neat row of heaped cane reeds are left in one perfect row in the centre of six.

They start at 5am, of their own volition and work until about 11am, to take advantage of the coolest part of the day. In some cases they will even prefer to work at night, during full moon adding a dramatic picturesqueness to it all - I would imagine.

The

sugarcane has already been burnt a day

before and it has rained during the night before my visit, turning soot into ancient

war paint. Everything

became smeared with a diluted black: hands, faces, clothing. Little

flakes not fully combusted added texture.

The

sugarcane cutter has

great confidence in his

or her work. Their team

leader tells me that they would chase each other sometimes

to see who would finish

their rows

first. It's a matter of

pride.

In

Swaziland, there used to

be sugar-cutting

tournaments aired on

local TV, and the winner

stood in line to win a taxi!

Visually, I was drawn to their romantic clothing style, the soot they were covered in and their muscular strength and movement between the towering and fallen skeletal reeds.

On

a more symbolical

level,

I was exploring human

fragility and the cycle of life, death and resurrection.

Sugarcane became

a metaphor for our lives

and has its own

significant life cycle. Each year it is burned, cut down to the

ground and thereafter even poisoned to make it “suffer” in order

to increase its sugar content. Yet, it rises again in spring - like a

phoenix from the ashes, growing up to two meters in 12 weeks.

The burnt reeds are carted off and the life essence of the plant is crystallized from these as pure white sugar after a long process of crushing, diffusing and boiling, removing all impurities - an appropriate metaphor for resurrection and hope after adversity and tribulation.

The sugarcane cutters with their heads covered or hooded, their pangas scythe-like and depicted among the fallen sugarcane reeds remind us of grim reapers. Determined, they are still only there to do their job.

During my visit that week to the sugarcane cutters of Malelane, I made a most interesting trade

transaction. I wanted to obtain their dirty, old (and

amazing)

articles of clothing,

go back to my studio and try to create

fibre art pieces from these - an art genre that has long intrigued

me. I stumbled across a second hand clothing shop in town, which

was running a sale,

incidentally! I bought

mountains of articles of clothing and had a most exhilarating

(and sometimes scary)

bartering morning, the workers taking from my stash whatever they

fancied and there and then getting rid of their,

own,

tattered

rags, throwing them back into my boxes.

Oh, most

valuable possessions! Oh, art

materials!

These weathered rags

were the embodiment of

companionship

and allegiance

to

my sugar cane cutters. Clothing's

closeness to the wearer's body, always worn within the wearer's

milieu

becomes one with body movement, living and working.

They travelled home with

me as a personal part and token of my workers. Back

in the studio, these articles were taken apart and something

new was created from them

- dirty, besmirched and

sweaty, just as I received them.

"Man IV" 's clothing was used in

both "Land II" and "Land III", fibre artworks.

Above, in "Land II" it can be seen in the little blue and pink parts showing themselves in the lower right corner.

The

worker pausing at his work

in "Man IV" is

a strong and proud figure, accolades

which he both deserves AND requires

for his gruelling seasonal work. Many of these workers are migrant

workers and have farms of their own which they attend during off

season.

Work, and waiting, waiting and work, it may not be an abruptly ending linearity, but I imagine (and hope) for it to be rather a circular and never ending cycle like life, death and resurrection.

In

a poem from his publication Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman, after

observations of graveyard grass, aptly describes our ending as he

sees it: “All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses and to die

is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.”