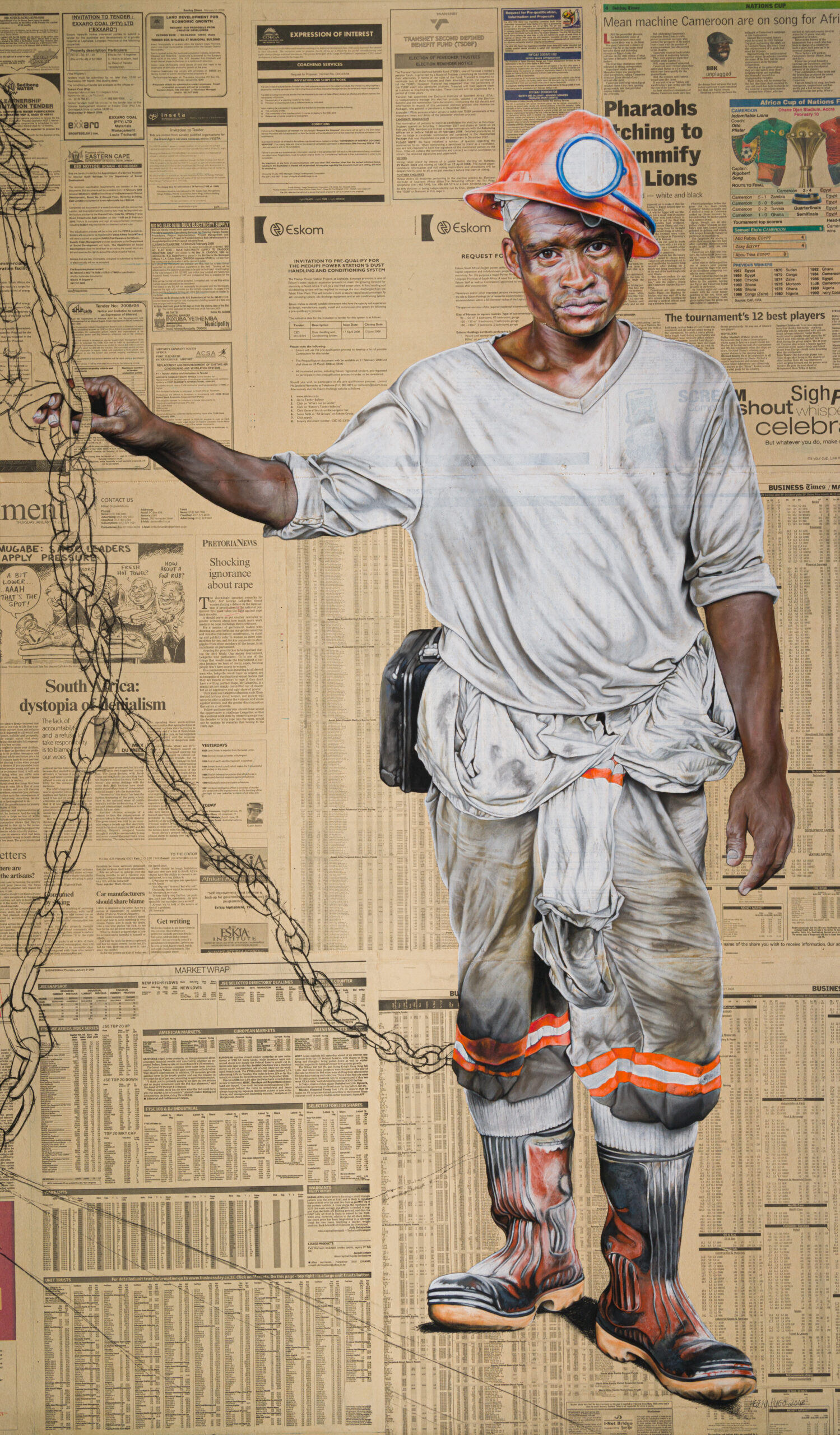

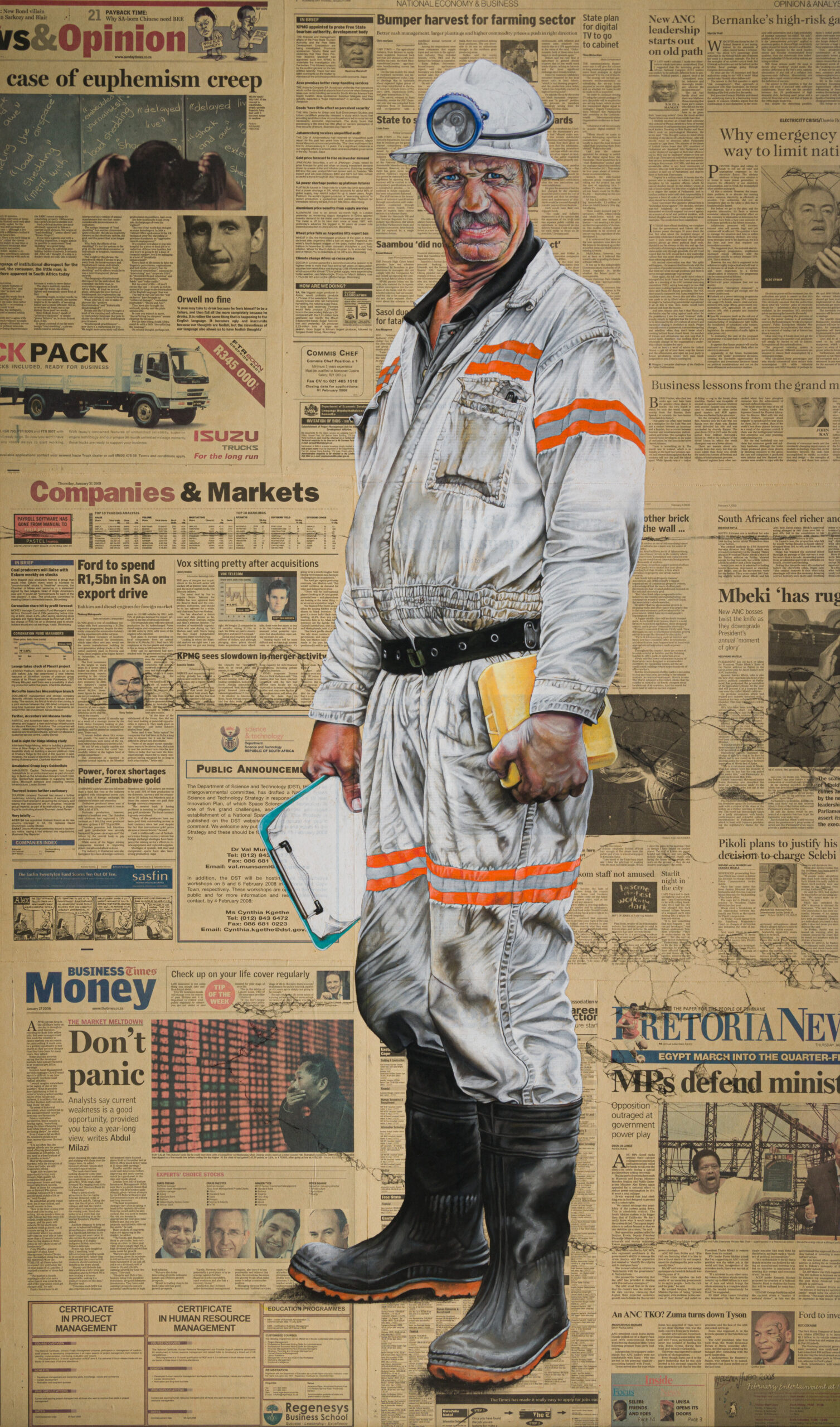

Miner I & II

Pastel and newspaper laid down on board

168cm x 98cm each

2008

On loan from Ukwazi Mining Industry for

Working Life in South Africa: Gerard Sekoto & Lena Hugo

Once a particle is inside the horizon, moving into the hole is as inevitable as moving forward in time - Wikipedia

It wasn't a true event horizon I was facing, camera ready for my first sighting, because light did escape from it at intervals. First the bobbing of a hard hat, then the head lamp, a gaze fixed on the ground, shoulders, torso, belt. Left hand and right hand with gloves. Knees, boots. The matter the entity was made of was flesh. Enveloped in pure white cloth, powdered with imperfections of dirt grey stardust.

Nobody knows what

goes on in a black hole. Neither did I go in that day to see. My

business was with the figure in natural light.

Besides, I've

been in a mine before, well sort of. And I still have a slight

case of post traumatic stress and fear of enclosed spaces.

As

very young children, we were forced down a hole at Gold Reef City, as

part of a school outing. I recalled being one of the "late

comers" (not my fault, I was in the last cage ride down filled

with children packed like sardines).

As a consequence I ended up

right at the back of the bundle of kids, gathered in the mouth of an

artificial cave. Hearing even a single word of the tour guide's

presentation was... an impossibility.

What she wás saying was that an illustration will shortly be made of the volume of noise that miners have to endure, during working hours, and please to put your fingers in your ears right now - which I did not do.

A man equipped with a massive drill was stationed right behind me.

It was so dark down

there and the man so frozen in readiness for his

task, that I didn't even notice him when I tumbled into the cave.

So

it happened that I was caught totally off guard when the earth

suddenly began to rattle and quake and rocks came shooting down from hell to crush my small yellow coated body. The

sound was horrendous.

This, in effect, didn't really happen, of

course. It was 'only' the example of the chaotic and terrifying

echoes inside a solid rock enclave with acoustics par excellence, effected

by a hand held drill, which sent my imagination into over drive.

But this was just the beginning of our forced trip down a hole where time stood still and infinite pressure and density warped space-time into a mathematical point: that of my little heart beating wildly throughout the rest of our torture tour.

It is said that the entire Marikana mess was centred around the grievances of drill operators, one of the most dangerous positions in a mine, their work romantically exemplified by this clean, non-sweating man who unknowingly just scared the shit out of me.

On 23 January 2008, 26 years

after my yellow clad nightmare, I saw living people emerging from a hole, tired after their shift of noise, dust and heat. This was before Marikana, and long before the Margaret shaft in Stilfontein.

Time

surely have changed since the days when children crawled through mole

holes on their hands and feet, dragging baskets behind them, tied

with cords around their fore heads, some of them dying there, women

giving birth down there.

But even for legal miners, even today, even for grown-ups, it's a tough job, like many other jobs.

A friend who is old enough to have had to endure under the apartheid regime, certified as "non-white" during those years, pointed out the chain in "Miner I". Somehow this is the work on the exhibition which he is most drawn to. The miner looks chained to the wall, to the tunnel which drags everything to that infinite gravity of the hole.

Miner II, the shift

boss, also has his time in that hole, I would imagine, although I found him organising above ground. He has greater

responsibilities, but can cart back a much larger reward in his own

motorcar and cleanses his pores in his own bath tub, with warm

water, after the stresses of each day.

The ordinary

miners' biggest hampering to his or her safety during working hours

can often be traced back to the poor quality of their lodgings. They start a shift already exhausted.

Noise,

dust, heat.

Cold, filth, crime.

Debt, worry.

The newspaper sheets which forms the surface on which the drawings were realised may have been a legerdemain, a showing off of my skill in wallpaper pasting, at the time of creation. I can't always remember why I chose to do things. Never the less, besides the fact that newspaper is a wonderfully receptive surface for chalk pastel, I am struck, years later - and pleased - by its property to immediately place the artwork in an appropriate historical context.

Nothing much have changed. Yet, oh, so much have changed, so that I immediately rush out to buy more newspapers to work on, now, years later. Because who is to say that there won't be an end to printed newspapers too, someday soon.

I'm not surprised about the colour fastness of the pastel drawings. I've always had complete trust in the pure pigments of pastel, mixed by the manufacturer with the minimum amount of binding material. But what surprises me, again about the newspaper, is its durability. (Remember, this is the first time in 15 years I see these works again). The gentle yellowing of the paper give the artworks an added richness and authenticity and accentuate the figures.

I've said before that this exhibition makes me emotional.

My children, my

miners. They went to Moria and back and like Bilbo am suspected of

having discovered the elixir of life, forever staying young, only yellowing a little from

the back, forever pulled up and out by a celestial light.