Portret 2011

A Portrait, as a

likeness of a person’s appearance, can tell us something about an

individual’s identity, by providing us with information regarding

their character, personality, social position, career, age and sex,

within the context of a specific time in the life of that person.

In the same way, it is possible that a group of portraits may portray

the identity of a society, a nation or a country within a given time

period.

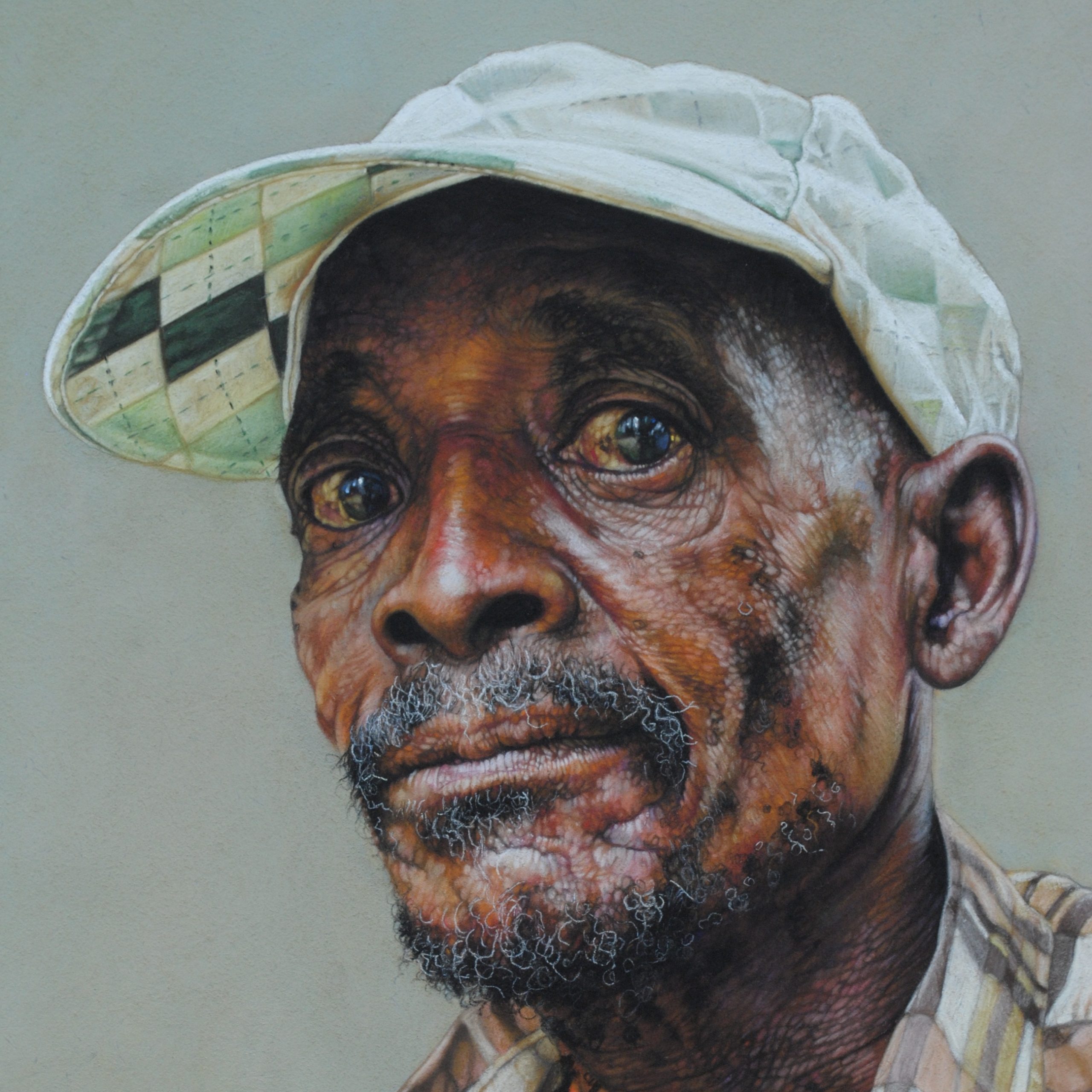

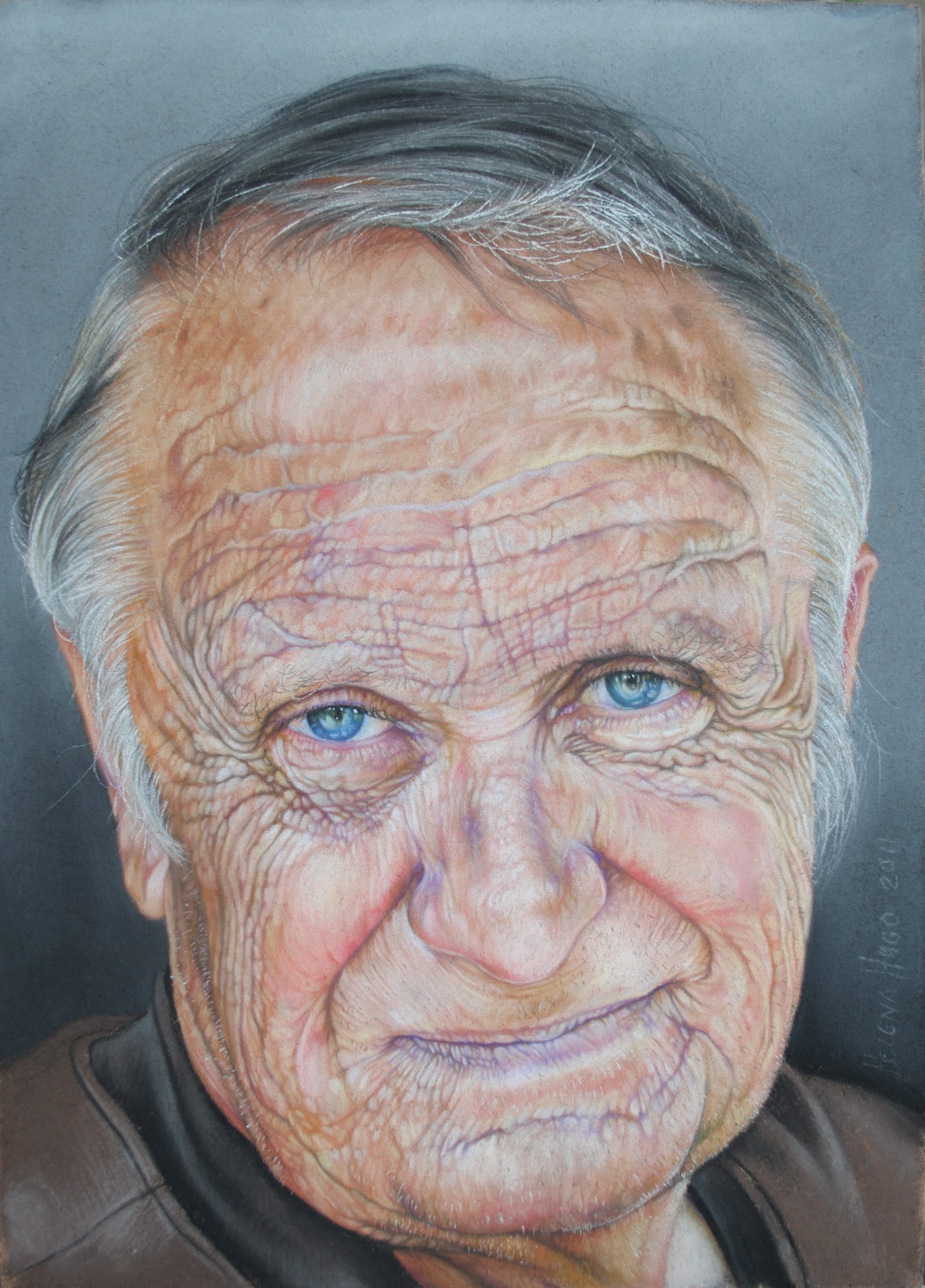

In an attempt to sketch the likeness of South Africa, Hugo offers us a group of likenesses which especially makes us aware of faces which we, depending on our own social status, may not always be aware of, though they form an important part of our landscape, economy, community and life.

In her portraits, Hugo tends to focus on the relationship between work and worker. Her portraits of workers in their working environments and of employment seekers, makes us aware of the importance of being employed. To have a job is an obvious necessity for survival and a way to overcome poverty and sometimes even crime, but psychologically it can have an even greater value. Research has show that a job can give a person a sense of value. Our personality and even our physiology may be influenced by the type of work we do. We obtain a strong clue to a person’s identity, when their type of employment are indicated in their portrait.

Looking at this exhibition in its entirety, we are made aware of a unified identity consisting of a multitude of talents and passions necessary for different kinds of work. It becomes a true South African portrait compounded from valuable individuals, each with their own pride and status.

Depending on our own point of reference, we experience these different likenesses as alien or in some of them, we recognize our own brother or sister.

There is always some kind of a relationship between sitter and artist. Excepting a posthumous portrait, both artist and sitter are present during at least a portion of the creation process. It then stands to reason that there was a degree of interaction between the artist and the individuals portrayed in this body of work. However if we broaden our gaze in such a way as to view this exhibition as a whole to be a compiled portrait of South Africa, the viewer’s position as co-resident and his or her interaction with the portrait on the gallery wall, in a measure, enables them to become a part of the creative process themselves.

2011 Absa KKNK, Oudtshoorn

Throwing Sand I

60cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Throwing Sand I

60cm x 60cm

Pastel on board Throwing Sand II

60cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Throwing Sand II

60cm x 60cm

Pastel on board Throwing Sand III

60cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Throwing Sand III

60cm x 60cm

Pastel on board The Dreamer

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

The Dreamer

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Work Seeker II

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Work Seeker II

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Patient

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Patient

80cm x 60cm

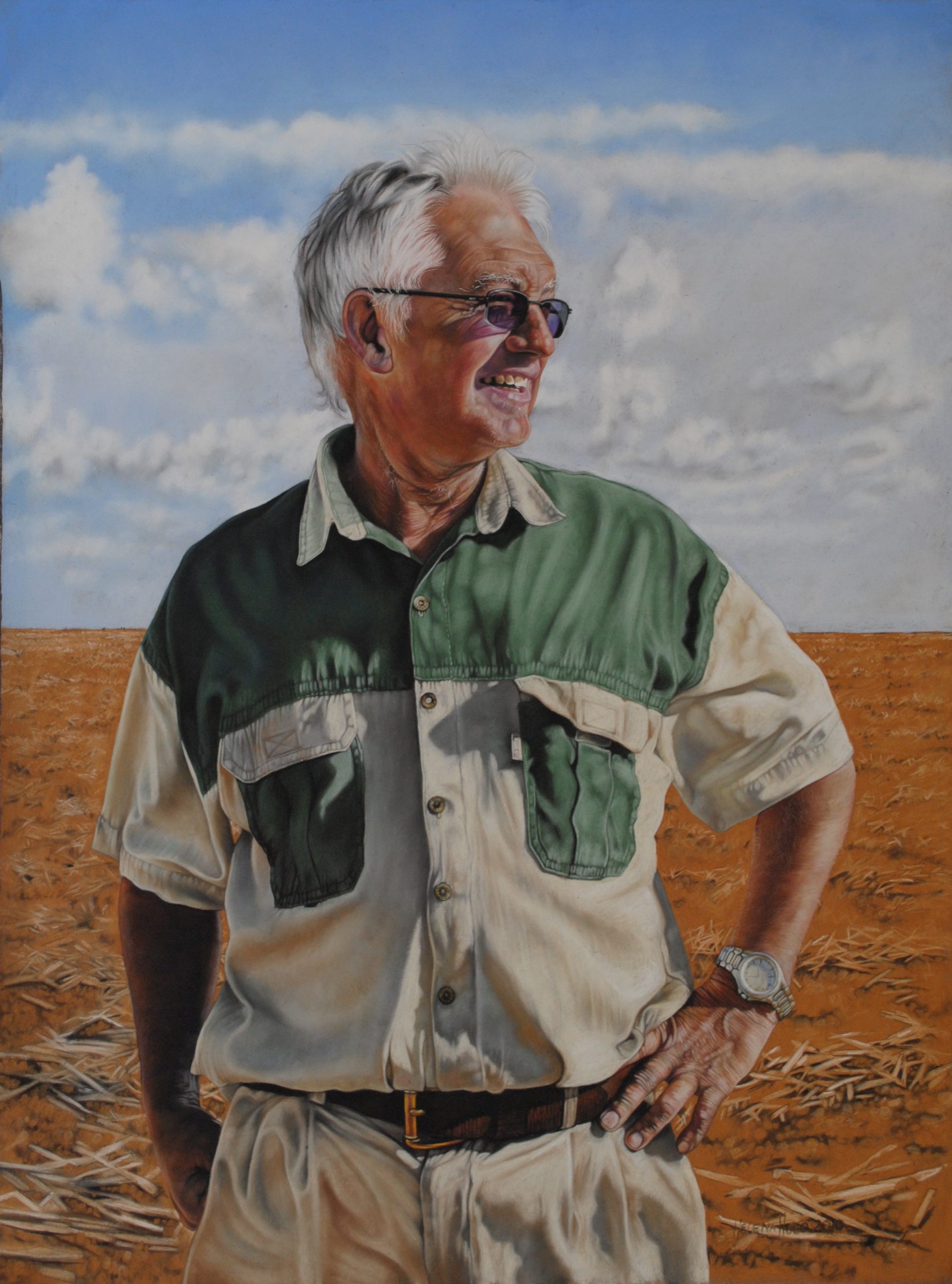

Pastel on board Farmer

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Farmer

80cm x 60cm

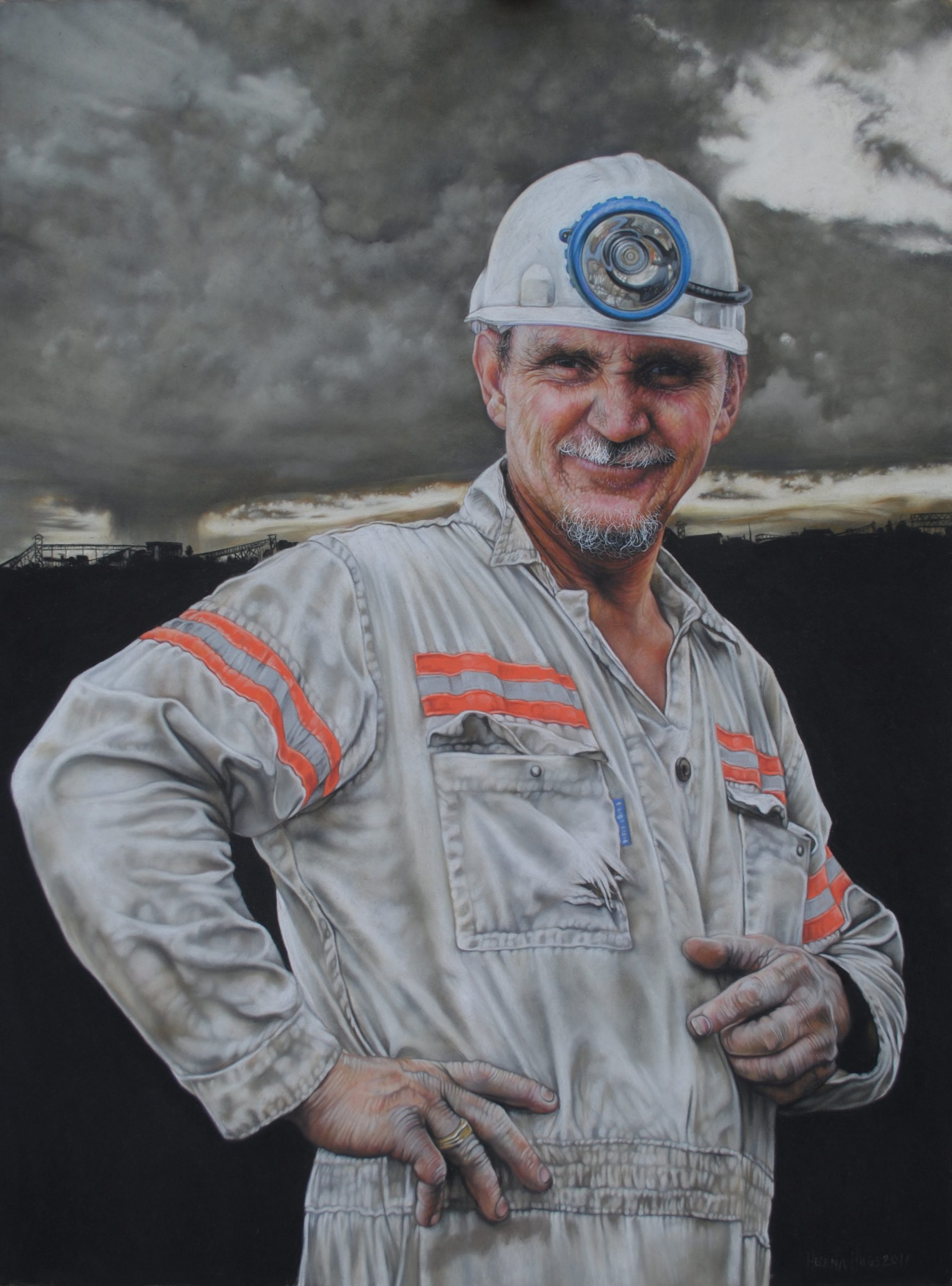

Pastel on board Shift Boss III

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Shift Boss III

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board News Seller

80cmx 60cm

Pastel on board

News Seller

80cmx 60cm

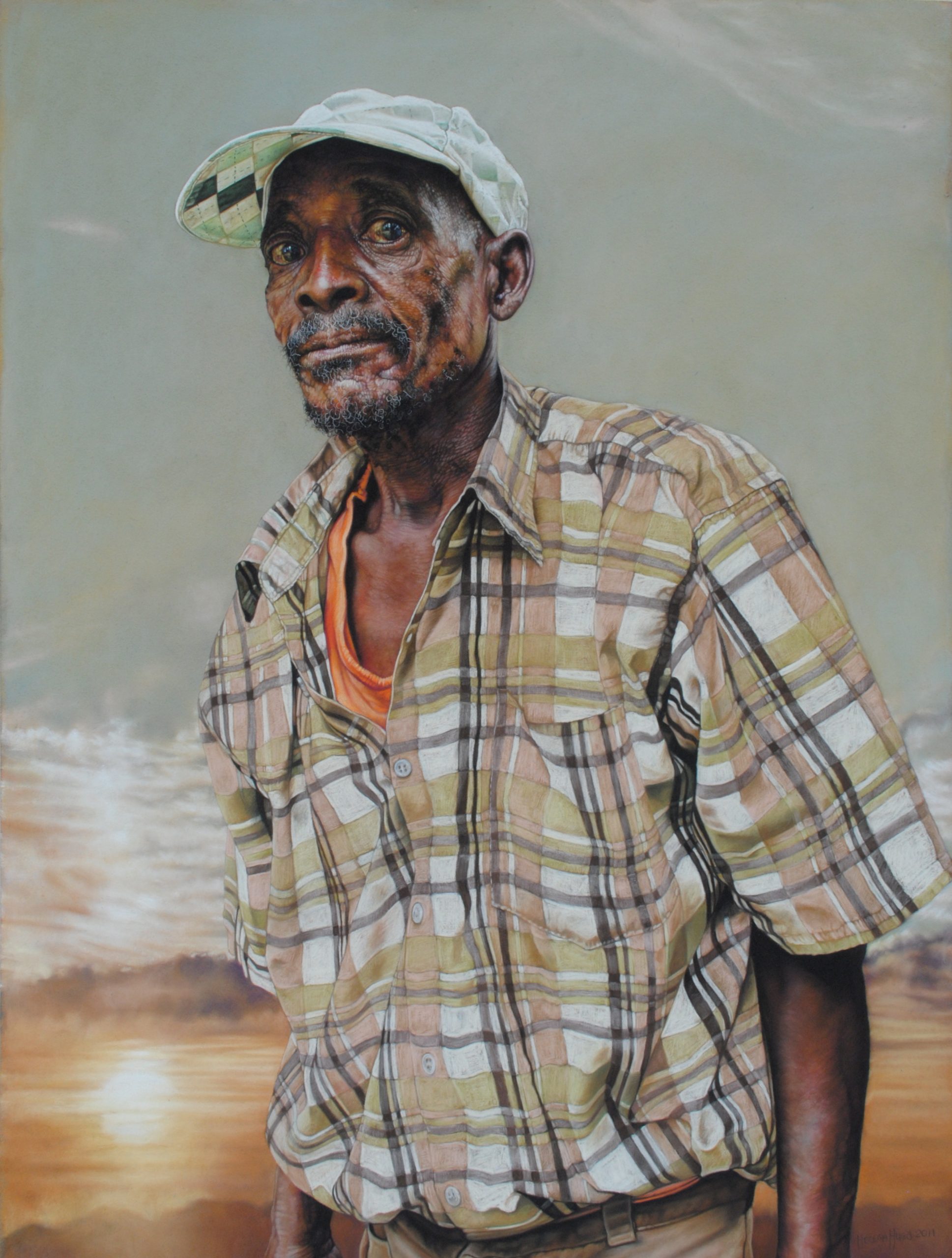

Pastel on board Work Seeker III

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

Work Seeker III

80cm x 60cm

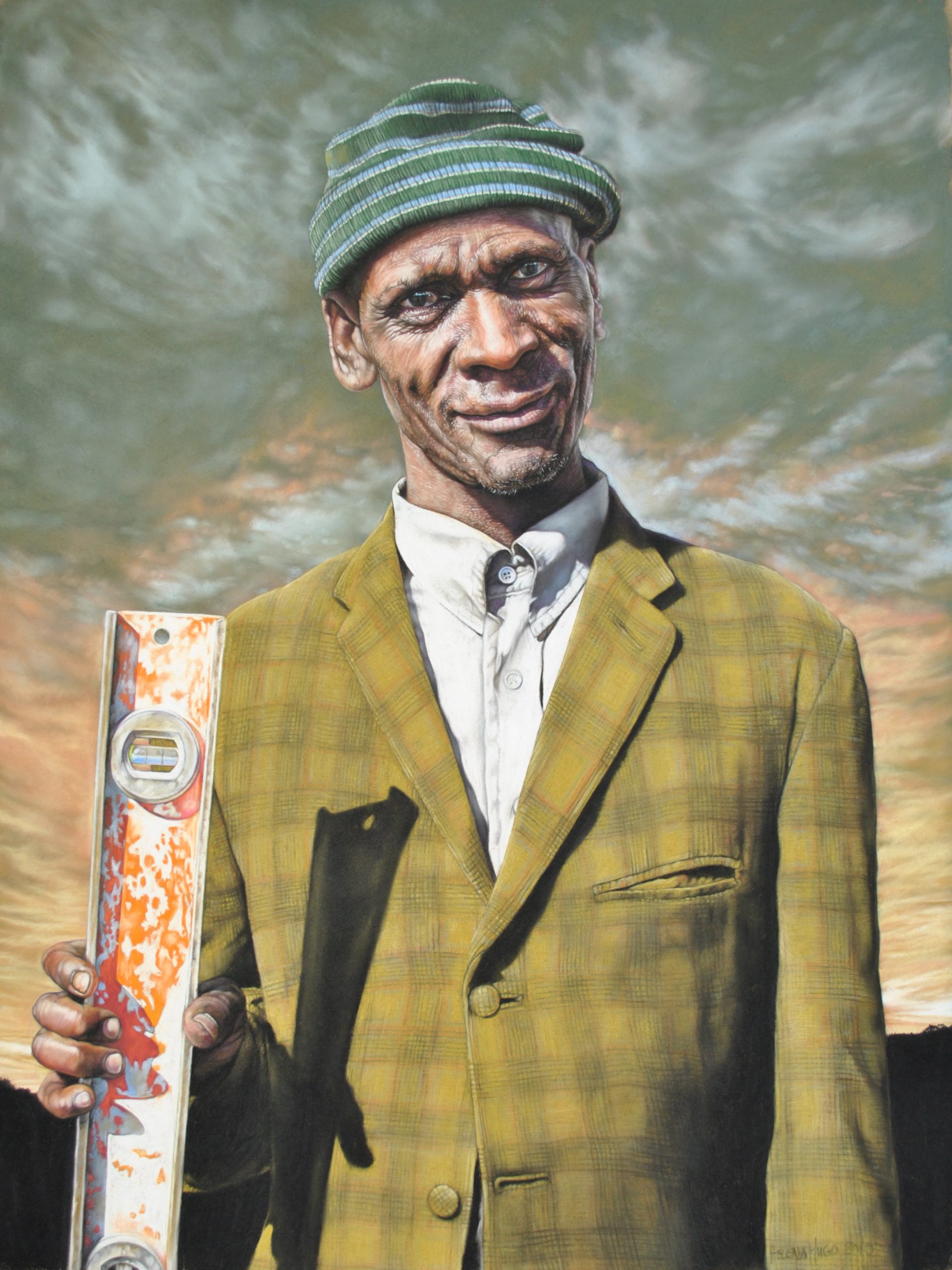

Pastel on board The Planner

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board

The Planner

80cm x 60cm

Pastel on board The Planner (detail)

The Planner (detail) Work seeker IV

127cm x 56cm

Pastel on board

Work seeker IV

127cm x 56cm

Pastel on board

School Bus Driver

35cm x 25cm

Pastel on board

School Bus Driver

35cm x 25cm

Pastel on board