Legacy 2019 - 2020

Legacy explores the unease we as humans experience with the idea of

the loss of “self” which can be equalled to the fear of death and

how it sometimes manifests in destructive behaviour towards other

humans, animals and nature.

It is often revealed in our need to dominate, change and rule over or separate ourselves from other humans and nature or to possess money, things, land or property, knowledge, prestige and even other humans.

It also becomes apparent in our need to be remembered or to leave a legacy.

For years Hugo has, through art, explored the frailty and transient nature of human life. With this exhibition she begins to explore the even greater precarious fragility of nature and the work also reveals a more conceptual tone. The transition was not a difficult one since Hugo believes that, in essence, to care about nature ís to care about people, especially the more vulnerable individuals of our society.

The works on the exhibition were a product of her time at a residency in Knysna, South Africa as well as volunteer work at “The flamingo project”, a rescue effort which started at Kamfers dam in Kimberley and soon resulted in a national rescue effort to help raise abandoned flamingo chicks.

In Legacy Hugo explores our natural heritage and that aspect of the ownership of land and nature, which is linked to habitat destruction.

She also questions the word “legacy” - an over used word.

What do different people consider to be the definition of “a legacy”? Could it sometimes just be material wealth and property or something that will make future generations remember the “I” in me? But in trying to achieve this, what happens to our natural heritage which belongs to future generations as much as to us?

The Kamfers dam situation in Kimberley was essentially a problem of habitat scarcity, habitat threats and habitat loss both directly and indirectly caused by humans. Even the severe weather conditions and droughts during that time were indirectly caused by human activity resulting in climate change and abnormal weather conditions.

The flamingo rescue effort not only saved the life of a number of near threatened birds, but with extensive media attention, had the effect of temporarily exposing local municipality irregularities, which could not be over looked or ignored any longer and caused reparations to be made regarding the neglected dam and nearby sewerage works.

Yet, a definite and enormous carbon footprint of its own has been left by the rescue effort. Such a rescue effort may unfortunately have its own negative aspects, affecting many other species on the planet and even the very future of Lesser Flamingos themselves. Not so much a vicious, but a, not so successful, circle comes in view, when looking at it from an all encompassing global scale.

Nobody can raise a baby bird better, cheaper and with a smaller carbon output than its mother and it will behove us to remember that prevention is far better than cure, that everything is connected and that every single day of our lives offers us endless opportunities in our own homes to make positive contributions towards the well being of all species.

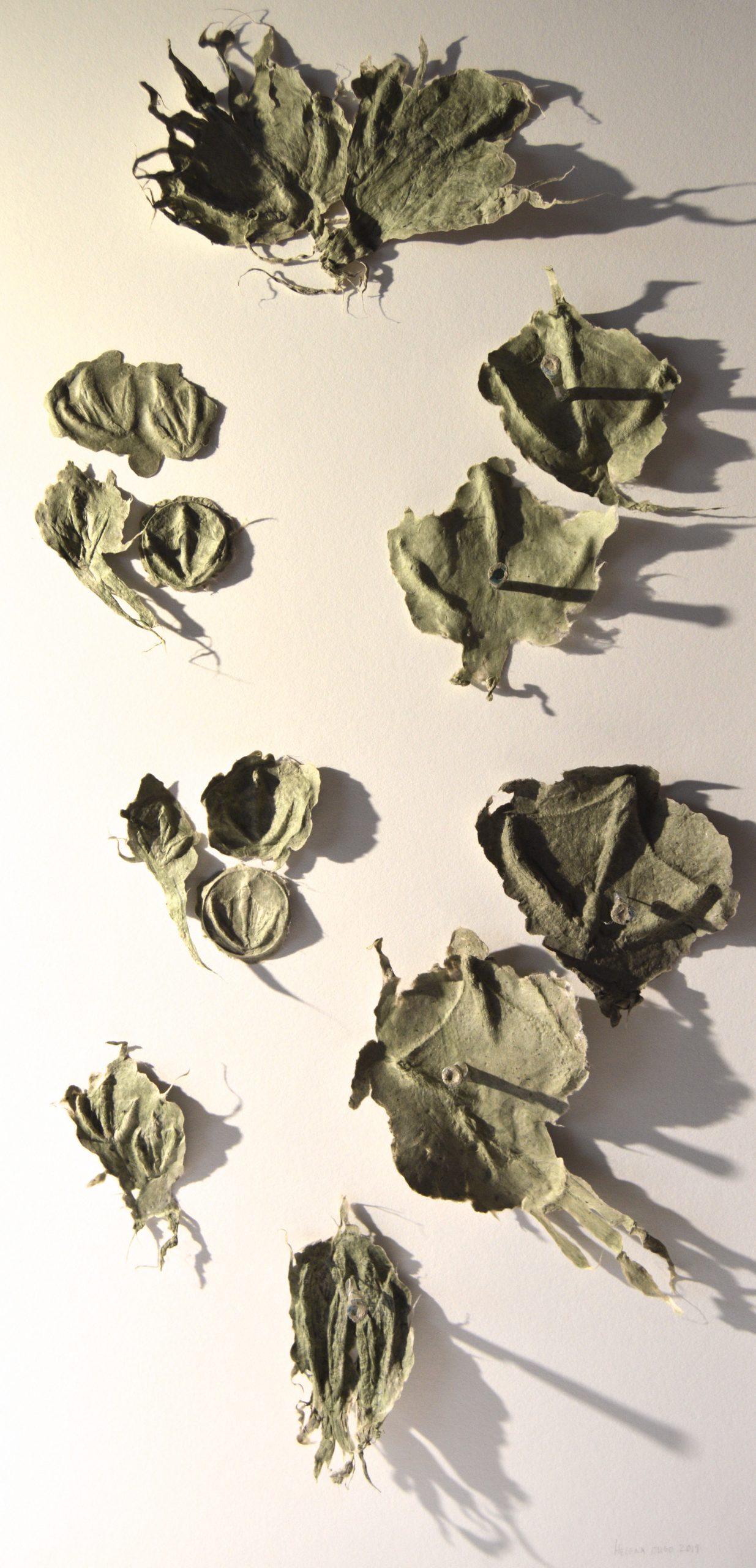

Visually there are two important symbols to be found in the exhibition - clothing and the human skeleton. Also algae, the staple food of the Lesser Flamingo, is used as material in some of the works and most of the work take on a greenish hue.

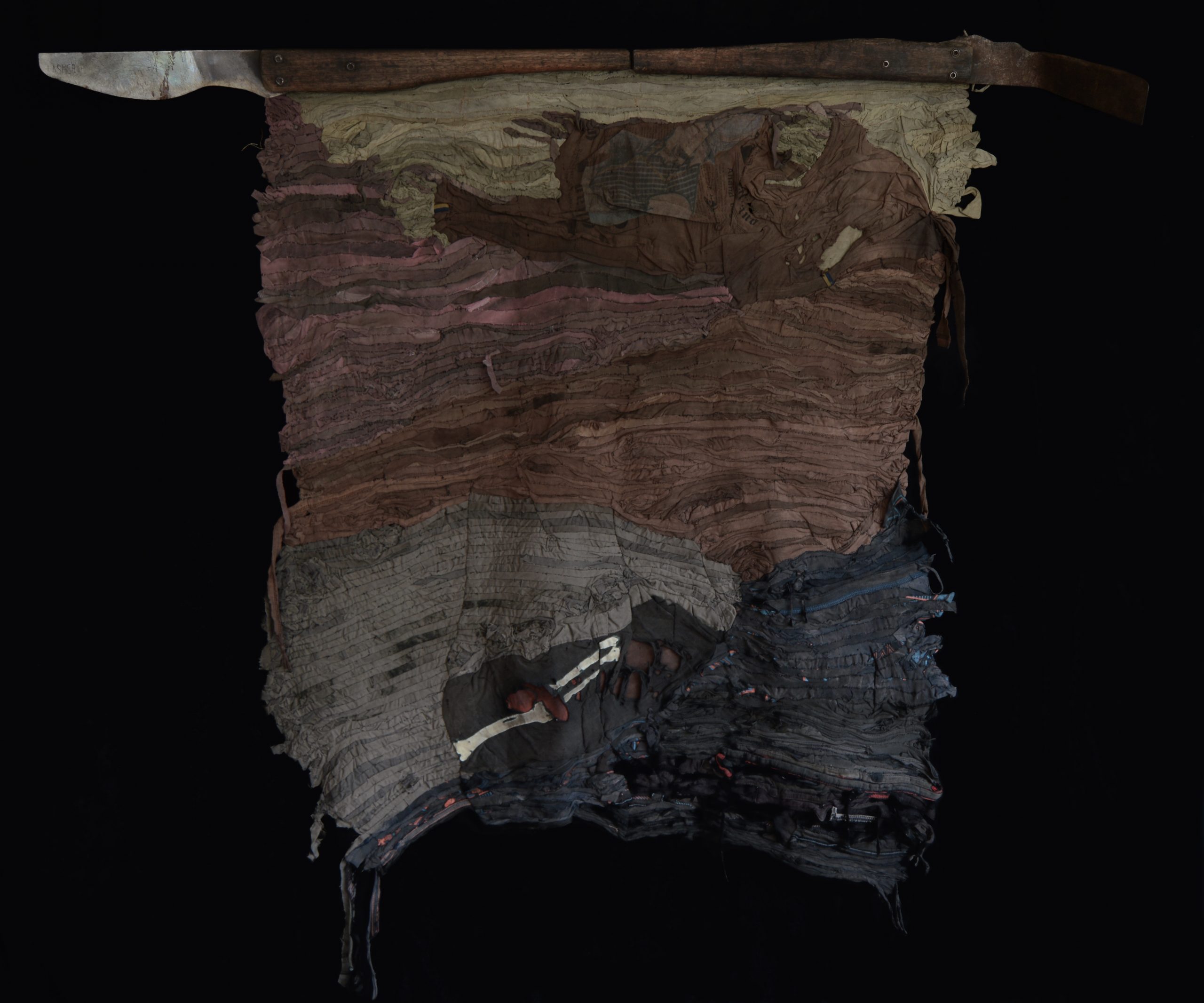

Clothing, which in this exhibition, is a metaphor for human possessions, was obtained from migrant sugar cane cutters in Mpumalanga and used to create fibre artworks. A shirt used as subject matter in some of the paintings was previously owned by a migrant farm labourer, working at the Knysna farm residency.

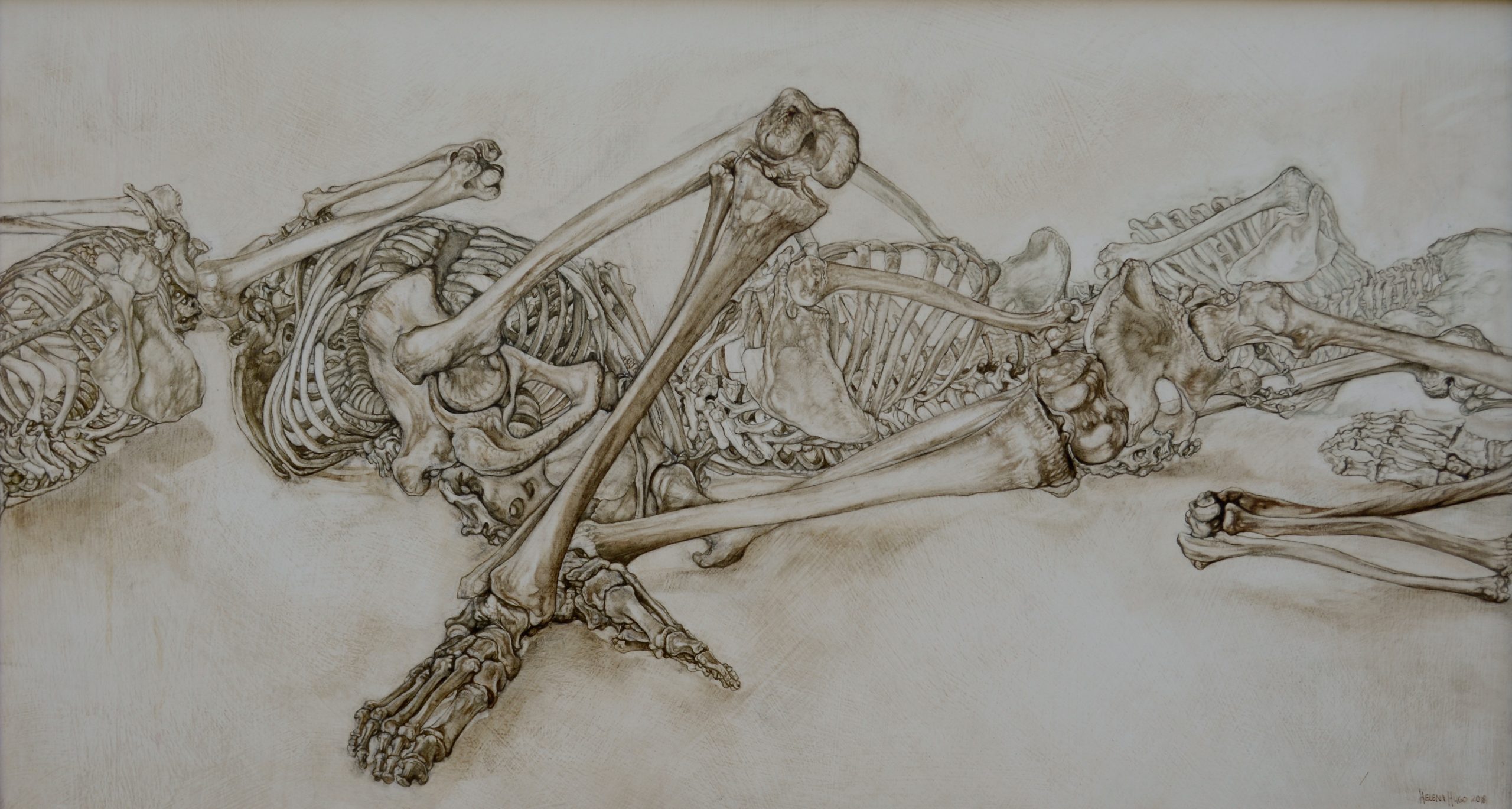

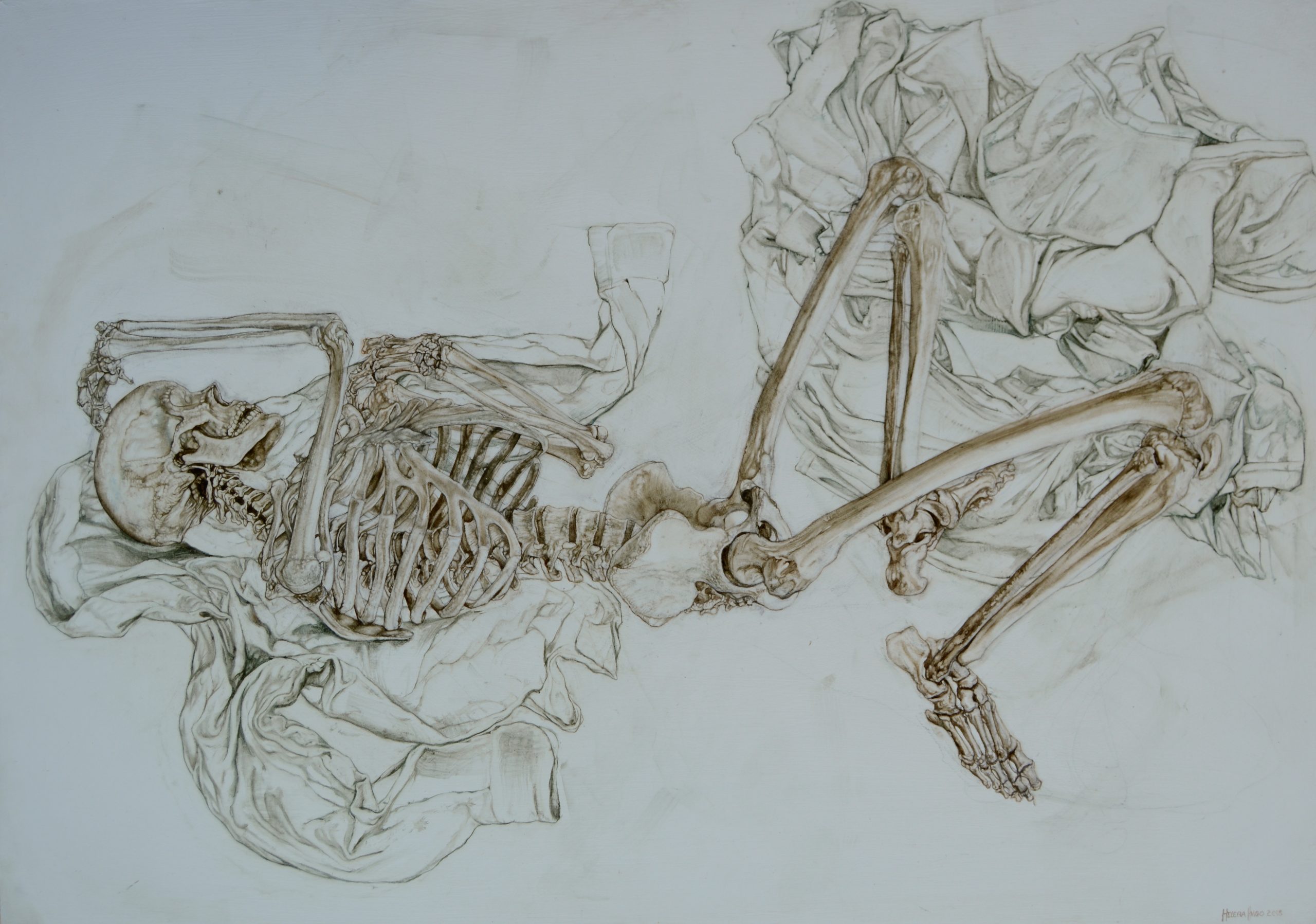

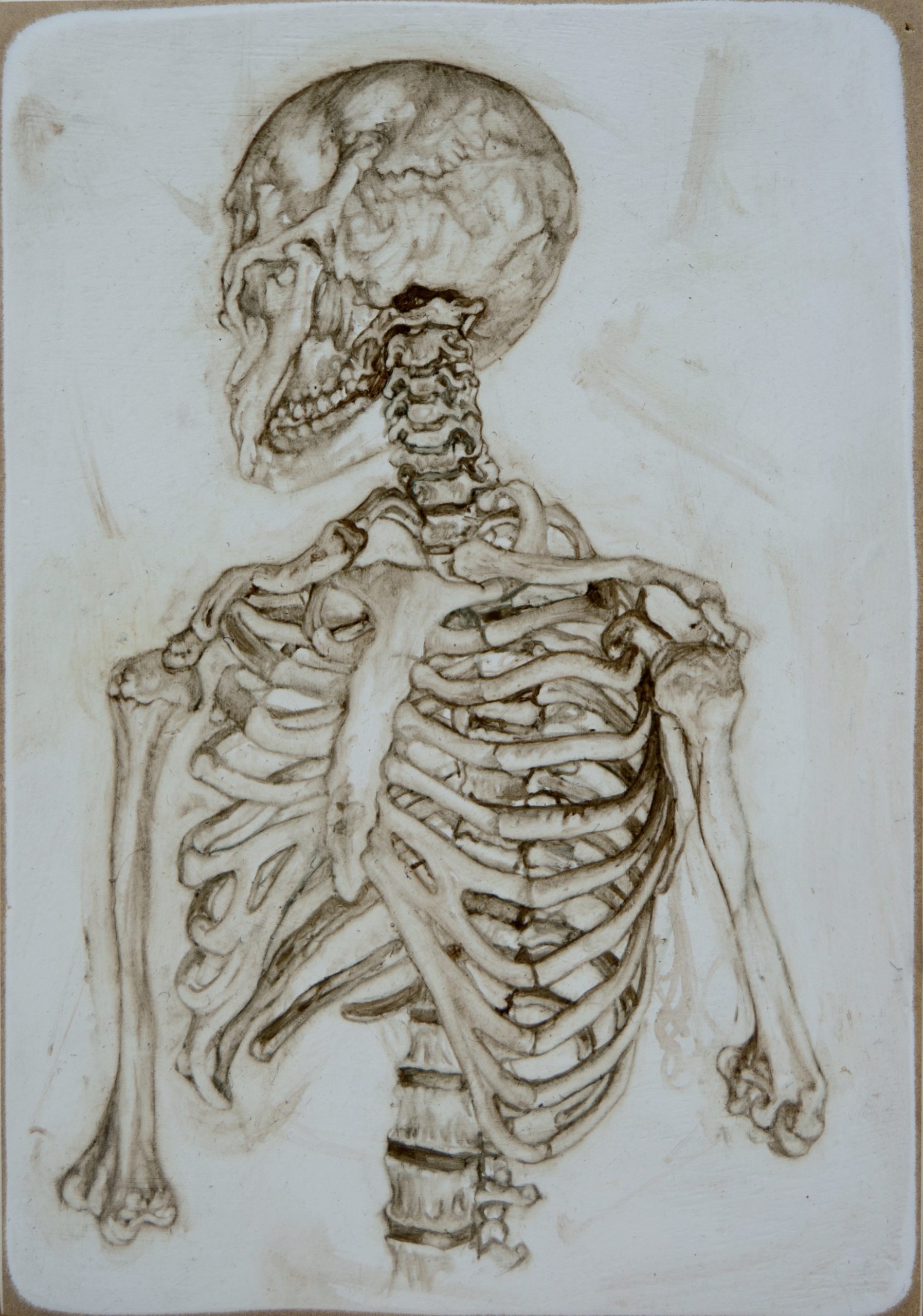

The human skeleton is a metaphor for death, heritage and legacy - that which ultimately will be left of us, by us, and for us, in the physical world and that which we may also be forcing onto our environment and fellow sentient beings.

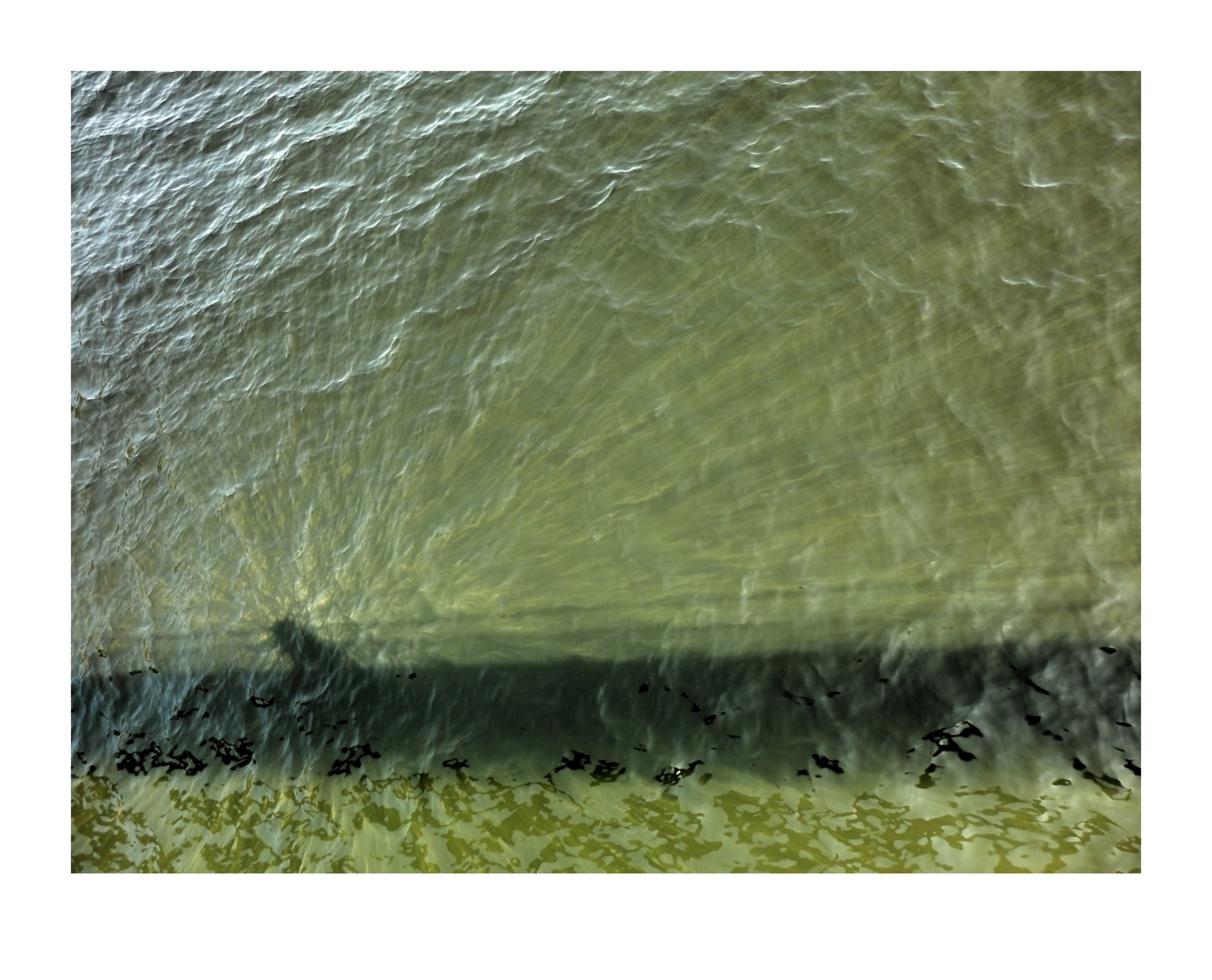

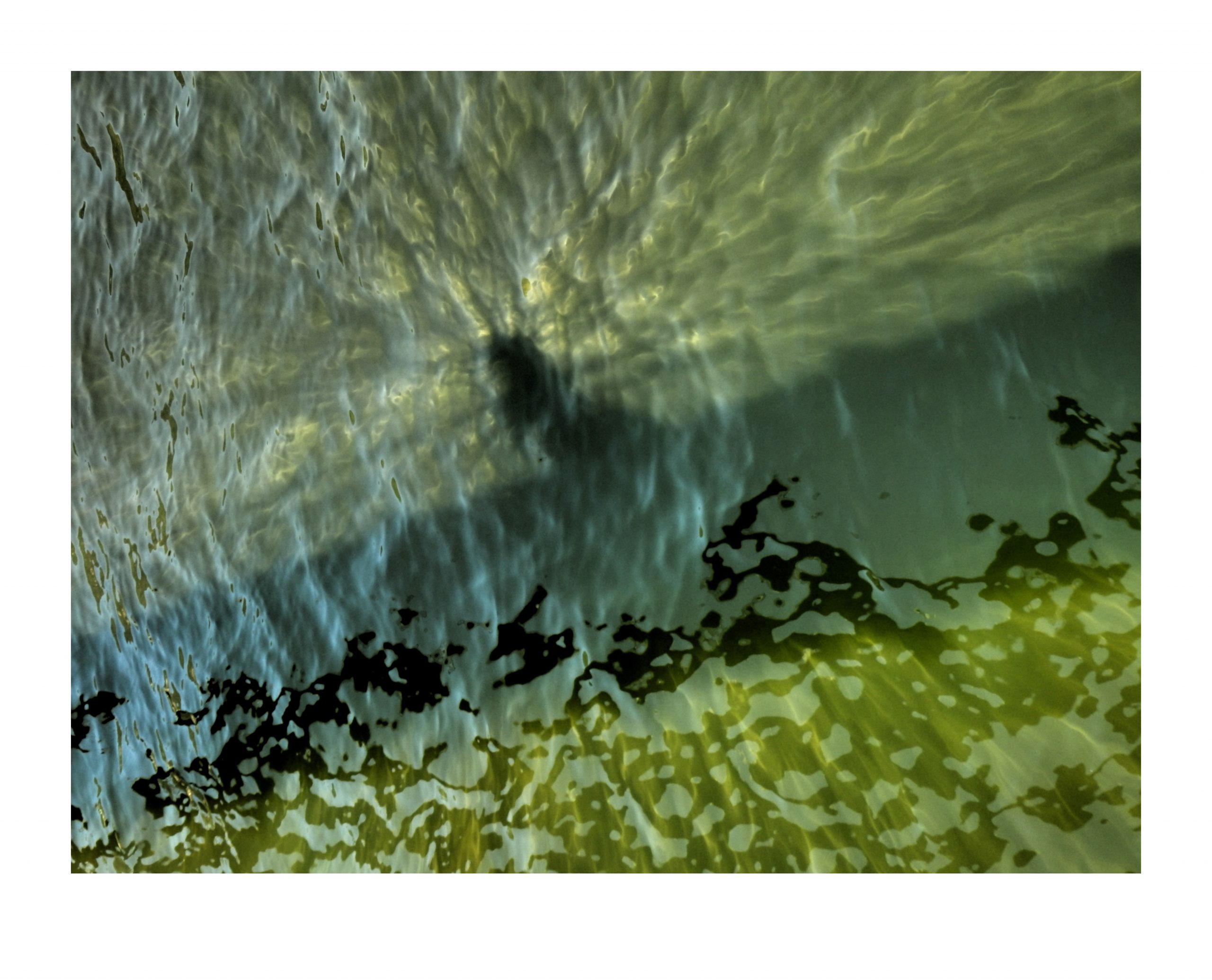

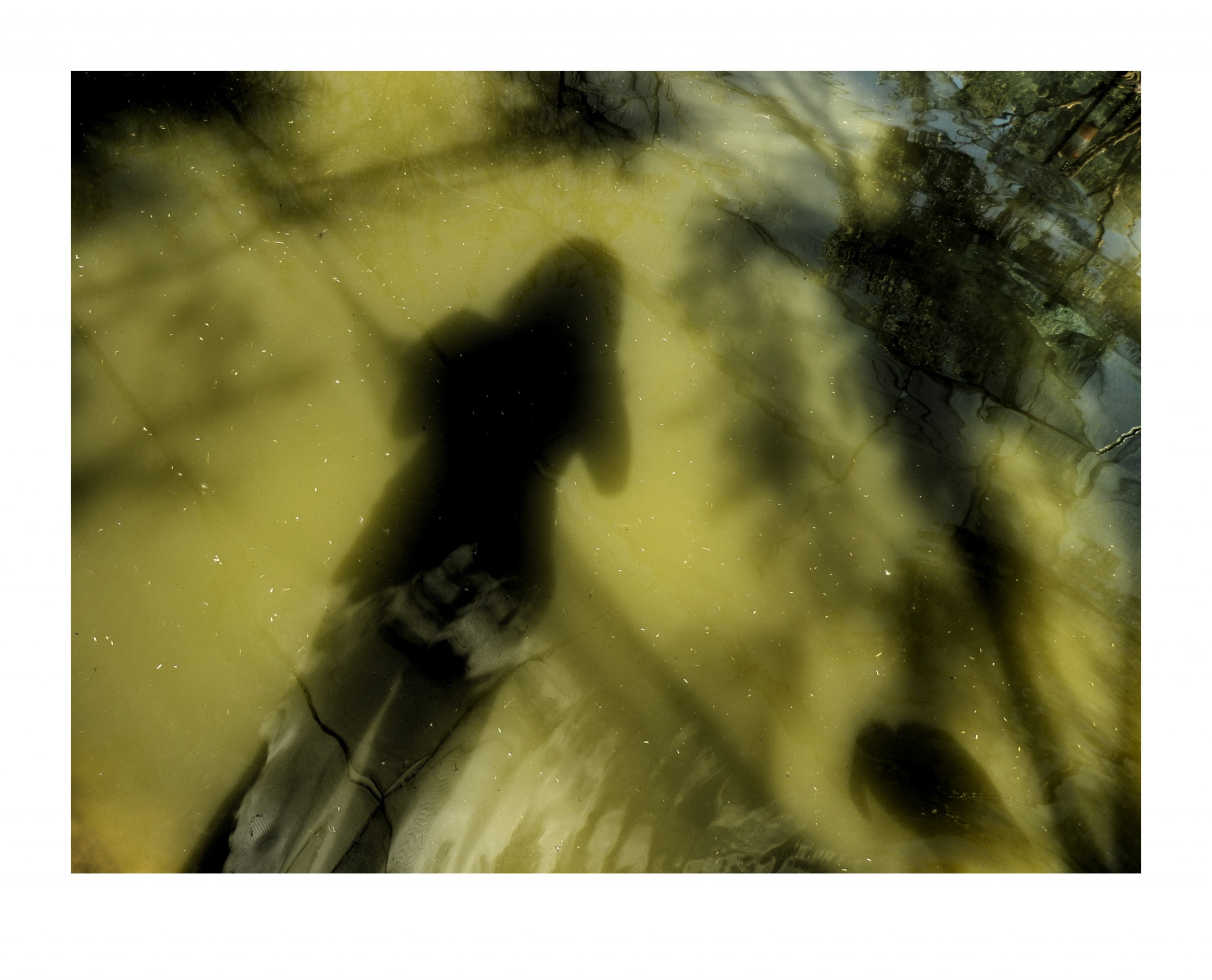

As algae reminds us of life as our main oxygen supplier and an important role player during the beginning of life on earth, so shadows, reflections and imprints are vehicles to convey impermanence.

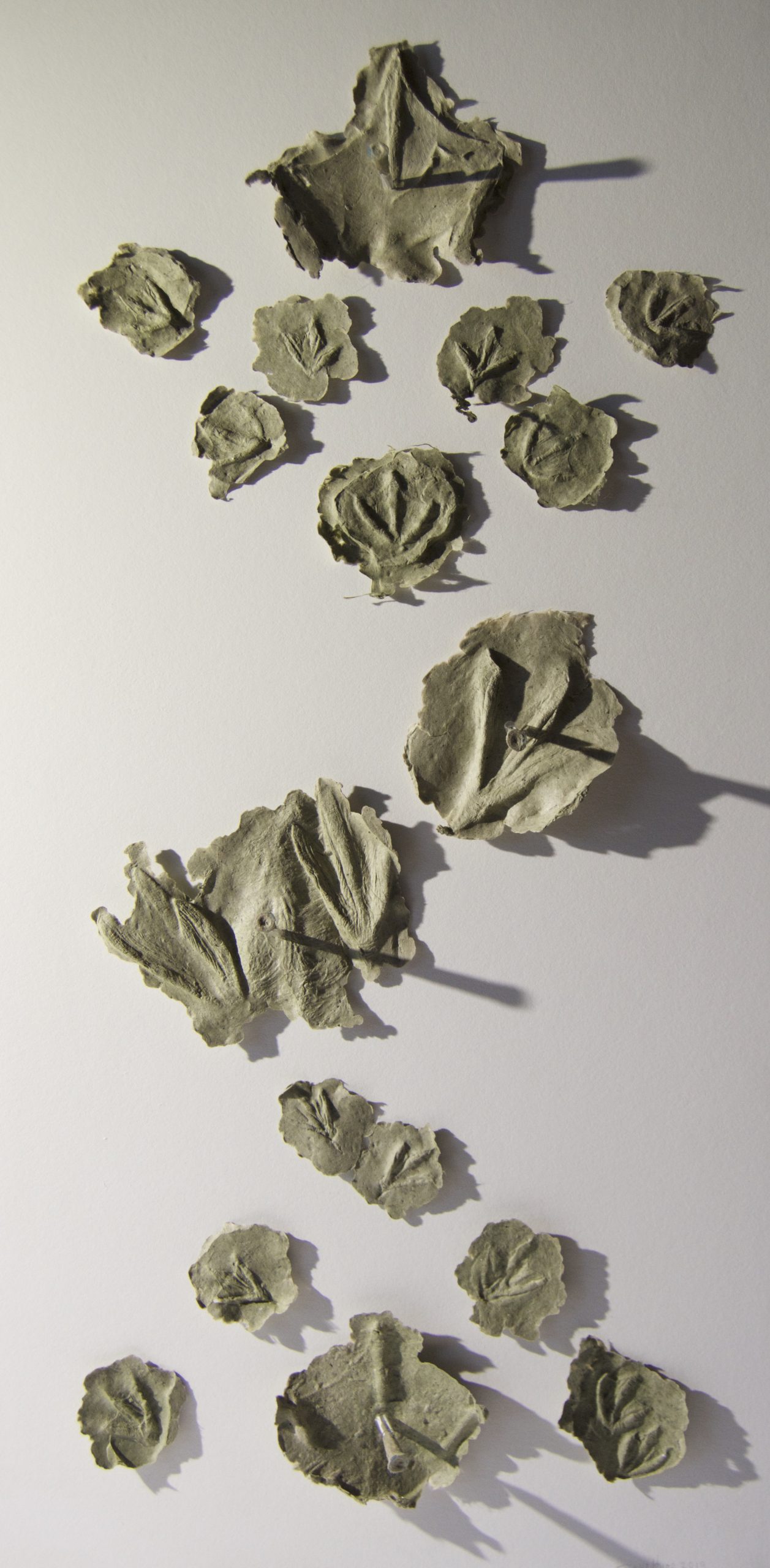

There is a strong feeling of archaeology throughout the body of work. Layers of soil are portrayed in the fibre art pieces and embossed paper works, almost like layers of meaning or earth memory. The process of collecting flamingo footprints, had of itself the ambience of archaeology. Feet imprints were gathered from live and deceased birds by using quick drying, non toxic alginate. Imprints were then translated into plaster and carefully stored in drawers and catalogued by each bird’s implanted microchip number for later reference and use. It would be interesting to know which of those birds are still alive today.

Hugo reminds us of the fleetingness of our own and all other life forms. Homo sapiens has only been on the earth for the past 200 000 years. Measured in a 24 hour day, we “modern humans'” history can be counted in 1 second. We are but an afterthought in an extraordinary creation drama which took the universe billions of years to bring thus far.

Yet, in the past 70 years, we have caused damage to life on earth quantitatively never experienced by our planet before. The steward, Homo sapiens received this legacy as a temporal gift which should be handed over to the next generations in good order, and yet we are destroying this legacy at an alarming rate.

12 - 31 July 2019 Association of Arts, Pretoria

30 January - 13 March 2020, William Humphreys Art Gallery, Kimberley

Land I

130cm x 140cm

Sugar cane cutter clothing, thread and pangas

Land I

130cm x 140cm

Sugar cane cutter clothing, thread and pangas Land II

130cm x 140cm

Sugar cane cutter clothing, thread and pangas

Land II

130cm x 140cm

Sugar cane cutter clothing, thread and pangas Land III

130cm x 140cm

Sugar cane cutter clothing, thread and pangas

Land III

130cm x 140cm

Sugar cane cutter clothing, thread and pangas Land IV

130cm x 140cm

Sugar cane cutter clothing, thread and pangas

Land IV

130cm x 140cm

Sugar cane cutter clothing, thread and pangas Land Memory I

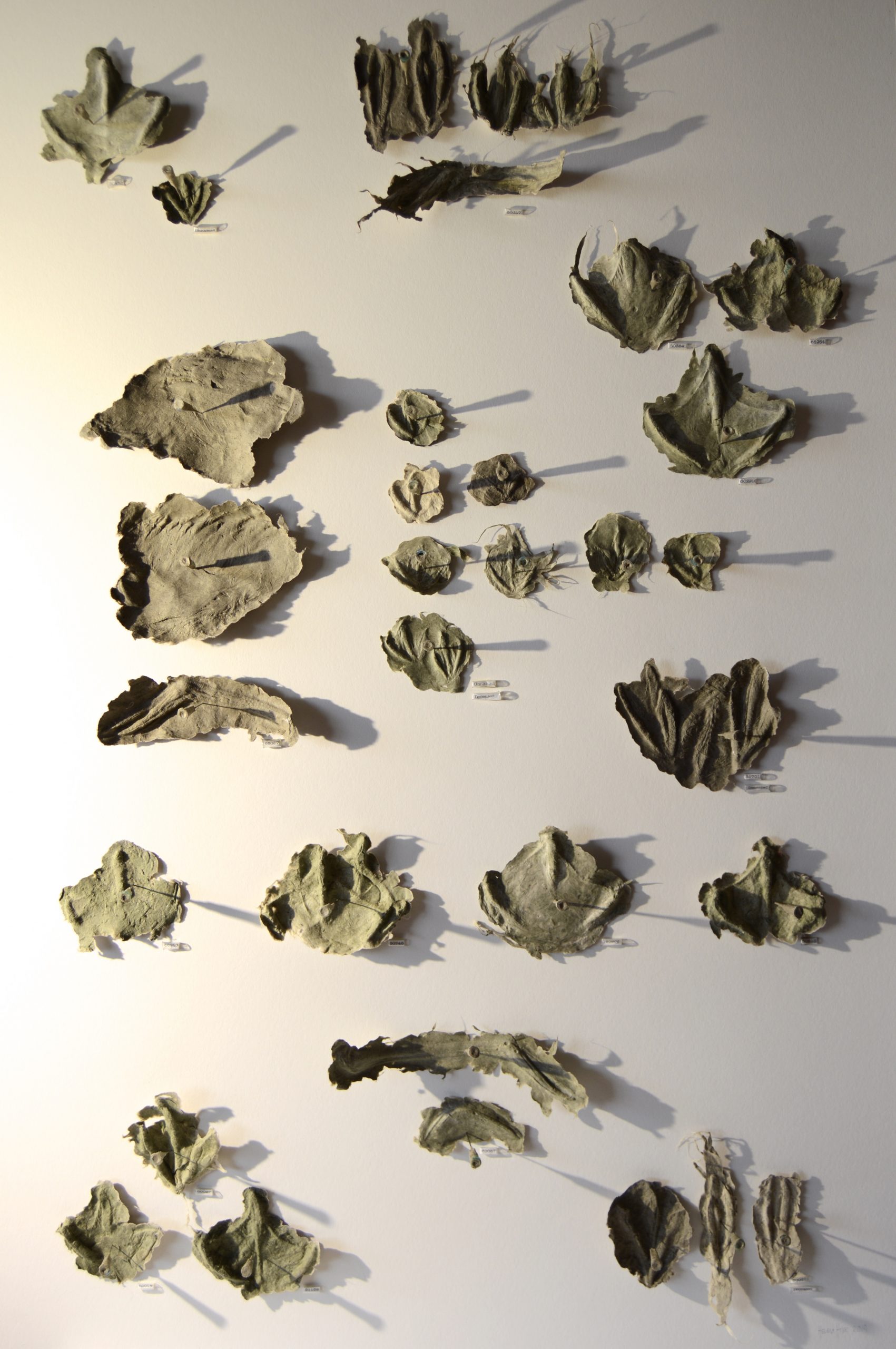

110cm x 160cm

Embossing and paper sculptures

Land Memory I

110cm x 160cm

Embossing and paper sculptures Land Memory II

110cm x 160cm

Embossing and paper sculptures

Land Memory II

110cm x 160cm

Embossing and paper sculptures Land Memory III

110cm x 160cm

Embossing and paper sculptures

Land Memory III

110cm x 160cm

Embossing and paper sculptures Skeleton with crossed hands

50cm x 100cm

Oil on board

Skeleton with crossed hands

50cm x 100cm

Oil on board

Clutter

75cm x 41cm

Oil on board

Clutter

75cm x 41cm

Oil on board Inheritance I

60cm x 85cm

Oil on board

Inheritance I

60cm x 85cm

Oil on board  Little Skeleton III

18cm x 13cm

Oil on board

Little Skeleton III

18cm x 13cm

Oil on board Family Crest

60cm x 60cm

Oil on board

Family Crest

60cm x 60cm

Oil on board Possessions I

100cm x 76cm

Oil on paper

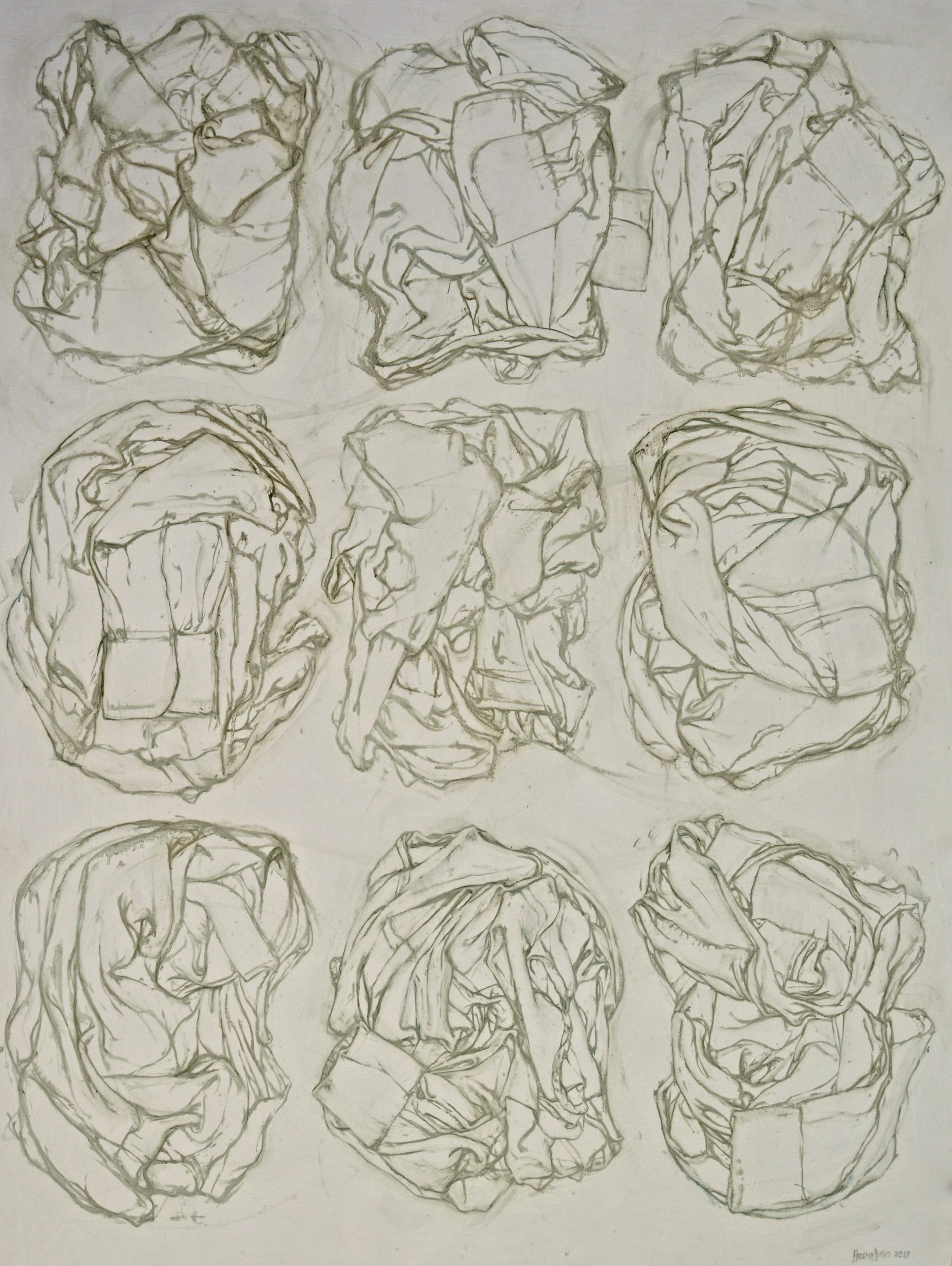

Possessions I

100cm x 76cm

Oil on paper Stuffed for Posterity

112cm x 100cm

Charcoal and pastel on board

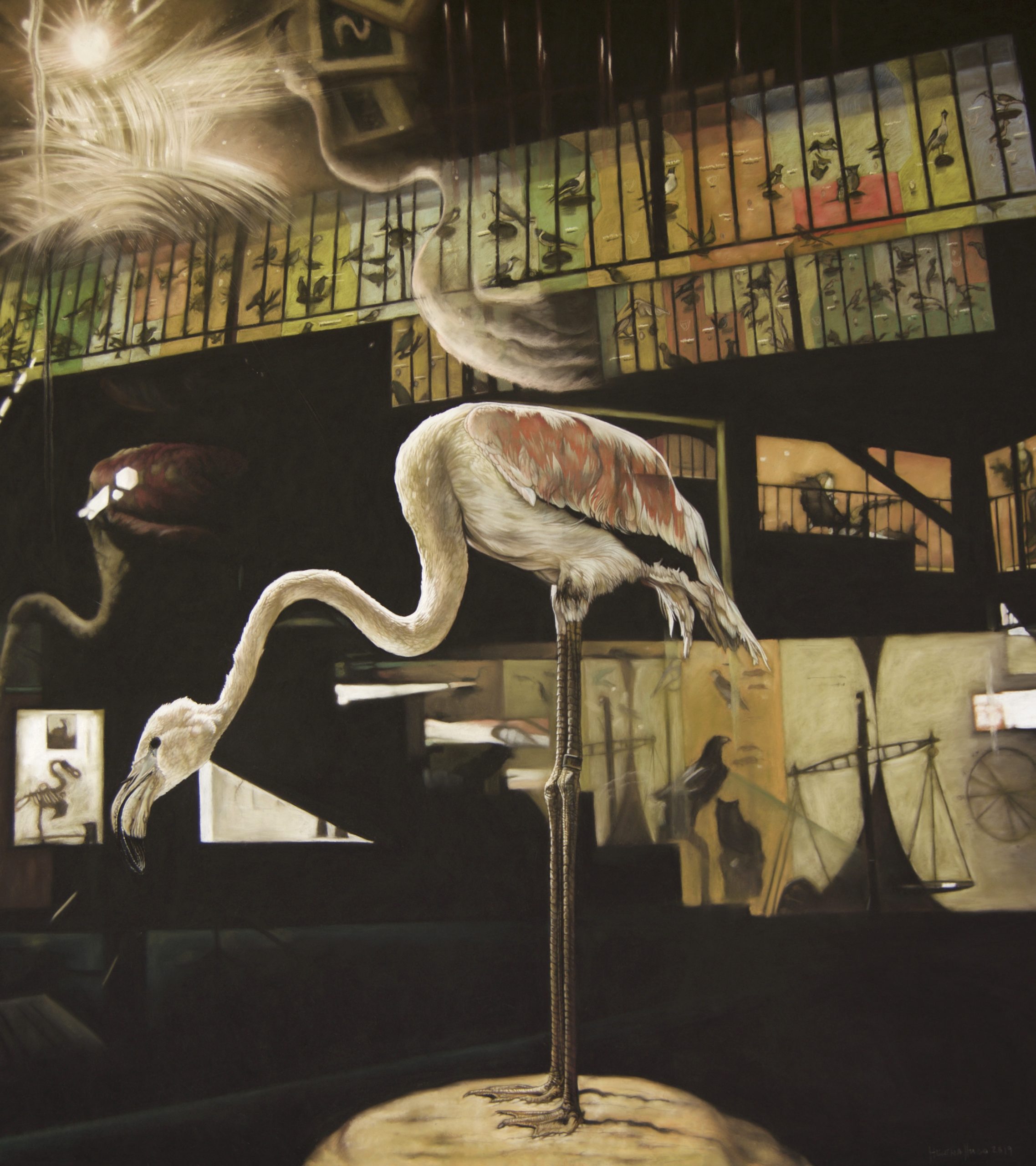

Stuffed for Posterity

112cm x 100cm

Charcoal and pastel on board The Butterfly Effect I

90cm x 60cm

Algae and hypodermic needles

The Butterfly Effect I

90cm x 60cm

Algae and hypodermic needles  The Butterfly Effect II

60cm x 30cm

Algae, and hypodermic needles

The Butterfly Effect II

60cm x 30cm

Algae, and hypodermic needles The Butterfly Effect III

60cm x 30cm

Algae, and hypodermic needles

The Butterfly Effect III

60cm x 30cm

Algae, and hypodermic needles Self Portrait as a Fleeting Thing I

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3

Self Portrait as a Fleeting Thing I

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3 Self Portrait as a Fleeting Thing II

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3

Self Portrait as a Fleeting Thing II

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3 Self Portrait as a Fleeting Thing III

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3

Self Portrait as a Fleeting Thing III

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3 Self Portrait with Flamingo as Fleeting Things I

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3

Self Portrait with Flamingo as Fleeting Things I

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3 Self Portrait with Flamingo as Fleeting Things II

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3

Self Portrait with Flamingo as Fleeting Things II

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3 Self Portrait with Flamingo as Fleeting Things III

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3

Self Portrait with Flamingo as Fleeting Things III

45cm x 60cm

Photograph on archival paper, edition of 3